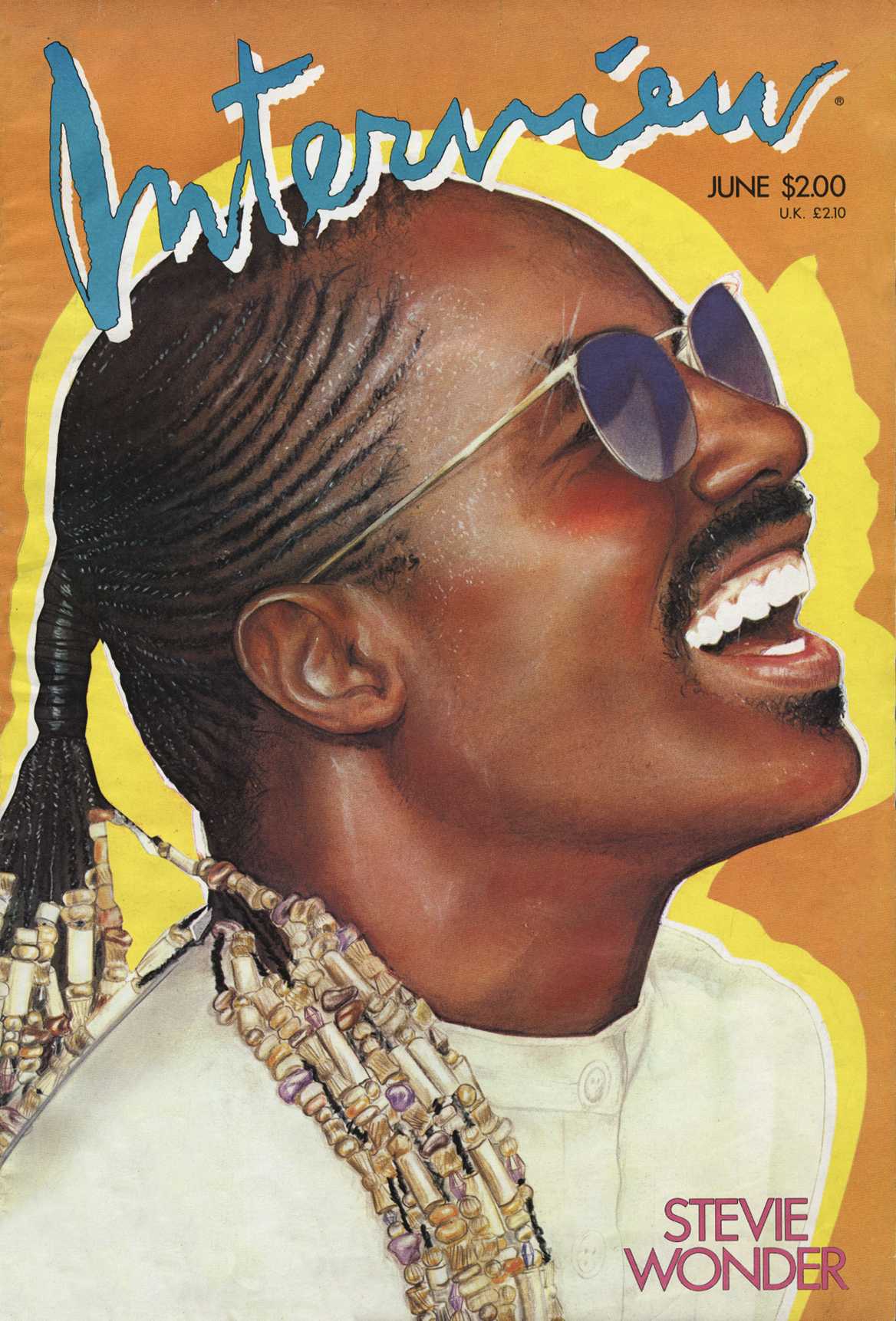

At this year’s Grammy Awards, Stevie Wonder was led onstage, head swaying beatifically from side to side, furrows of tightly pulled cornrows trailing back in a mass of beads and gold and hanging down his back like a psychedelic Aztec ponytail. It was, of course, a familiar image. Pausing at the podium, the play of light dazzling off white teeth, sunglasses and a tuxedo jacket of iridescent maroon, he delivered a few gracious remarks and walked off with Best R&B Vocal Performance for his latest album, In Square Circle—his sixteenth Grammy.

The running joke popularized by comedians like Eddie Murphy and by Stevie himself—“This is all an act, I’m not really blind behind these glasses”—derives its humor precisely from the enormity of his accomplishments. Almost a quarter of a century since a “nappy-headed little boy” form the Detroit projects named Steveland Morris became a household name in America as Little Stevie Wonder, “the twelve year old genius,” Stevie continues to astonish, provoke and delight. Today, at the age of 36, he has become much more than an extraordinary singer/songwriter, multi-dimensional musician and vanguard producer. As one of pop music’s true icons, Stevie Wonder has become an institution unto himself, a symbol of the can-do ability of human spirit to turn adversity into triumph, as recognizable around the world as Coca-Cola.

Stevie's life and career are once again peaking with an onslaught of events and projects. Earlier this year, for example, in the span of just a few weeks, he made a trip to Japan, sang at Diana Ross’ wedding in Switzerland, made an appearance on The Cosby Show, produced the television tribute on the occasion of the first observance of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday as a national holiday, attended several award shows and photo sessions, not to mention nonstop songwriting (he writes an average of one new song a day), producing, mixing, filming videos, commercials, et cetera. Small wonder that he’s developed a notorious reputation for being late, even weeks late (in fact, entire articles have been

written about waiting for Stevie). Spending time with him requires the patience of a Zen master and a willingness to remain in a sort of holding pattern around him—and it doesn’t matter if you’re Barbara Walters or Berry Gordy Jr. This isn’t arrogance, but perfectionism: If he has to do four things simultaneously, he wants to do all of them with total passion and commitment. He works marathon hours, stimulated by only his imagination and strong cups of coffee with honey, but sooner or later runs out of gas and crashes, and somebody is always left waiting for him while he replenishes his batteries. He lives his life in the singular rhythm of somebody who grew up blind and very successful in the entertainment business, for whom the passage of time from day into night is as irrelevant as it is unseen. Stevie can do virtually whatever he pleases, with complete creative freedom. And the bottom line is this: When Stevie finally shows and works his magic, nobody ever complains about the delay. His favorite restaurant in Los Angeles is Gitanjali, a small, elegant Indian eatery on La Cienega, where he arrives one evening, clad in black leather, in a beige Rolls-Royce chauffeured by his brother, Calvin Hardaway, and was led to his favorite table.

“Everything is in cycles,” he explains when I ask him why everything seems to be happening to him at once. “You look at the galaxy, and the earth and its rotation, the plants, the seasons. You look at everything, and we’re only a reflection of that. I feel very thankful to experience this response some 25 years after, you know, ‘Fingertips, Part 2.’ The industry itself is an even faster turnover situation now than before—things happen at a more accelerated pace, for shorter periods of time. The basis of music has always been pretty consistent. I’ve always tried to approach it as a new frontier every time I do a new song and just respond instinctively, like seeing something new in the sky through the lens of a camera—maybe something that you never expected because of a new angle.”

Cameras, angles, the image of the sky—that Stevie expresses himself so visually in conversation is a powerful irony, certainly a source of power in his music. In Square Circle, for example, contains a love fable called “Never In Your Sun.” The lyrical imagery is quintessential Stevie Wonder:

I met her at lovers’ park

One rainy April Monday

Smiling soft and warm as on

A clear December Sunday

Wearing tafetta and lace

That marched her braided hair

With their coraled beads

That sang to me. . . .

The question that mystifies: How does a blind man write about these romantic impressions more poetically, in some cases more graphically, than most sighted artists?

“With everything that I sing or say or write,” he explains, “I imagine it in my mind from association. The whole image of this person appearing in a park where there’s rain and a face that is very sad. . . . I guess it’s like a movie. Even though I’ve never seen these things, I’m there in my mind. ‘Cold December, her warm smile.' It’s like, in the Midwest, think of being home in December; it’s Sunday after church, and dinner’s cooking, warm vibes, sweet potato pie, and the family’s all there, and all of this matches with a person’s smile, it’s beauty, a hidden kind of joy. It’s a beauty that I’ve never seen, but it’s a beauty that I know . . . .”

And he laughs, his face tilted up as if it toward some cosmic rain shower splashing color against the palette of his imagination. It’s the laugh of a child, as if such wonderment is the simplest thing in the world to fathom.