The Cros is gone. Having dodged so many bullets, what a gift that he made it to 81…He was deeply talented, creative, intelligent, articulate, poetic, driven, committed, bold…deeply flawed but deeply honest about it and therefore deeply wise…and in the end and always, deeply, deeply human. All of which made for a fascinating man and a beautiful artist. I’ll always be grateful that he shared a bit of his life with me. Here ‘tis…

David Crosby strummed a chord on his guitar and the rich sound filled the living room of his Encino home.

“I was in full flower in ’85,” he said of his addiction. “There were a tremendous number of freebasers by then. We thought we were the Dark Side. We thought we were going to buck the trend. But that’s about when the turning point came, when it hit the streets as crack.”

Crosby hit another chord.

“I was a stone-cold junkie. Sores all over my body. Numerous car wrecks from having grand mal seizures while driving. Multiple seizures from toxic saturation. I’d tried several times to straighten out, six times in hospitals and at least four times on my own-all utter miserable failures, each of which made me less able to try it the next time. I was dead but still walking around. Stole drugs. Dealt drugs. Pleaded, begged, borrowed, and told any lie to get drugs. The only thing left was my wife, Jan, and we would lie down on our bare mattress on our bare floor, throw a blanket over ourselves, and just hold on to each other.”

Freebase is produced by mixing cocaine hydrochloride powder with ether and water to switch the drug’s pH back from acid to alkaline, reducing the substance to its base so that it can be smoked. As Crosby noted, “All basers are obsessed with it. They think they know everything about it. Basers imagine they’re chemists, scientists, doctors and pharmacists, and everybody has a slightly different theory about how to make it right.”

Scads of accoutrements are required: little pieces of glasses, tubes, bottles, stoppers, screens, pipes, pieces of rubber, scrapers, containers for liquids and powders, pH papers, water, ammonia, baking soda. And the all-important torch, of course. The problem with basing is that ether is highly flammable—and the higher you are, the easier it is to start fires, as Richard Pryor discovered on that night in 1980 when he ran screaming down the streets of the San Fernando Valley, engulfed in flames.

The second problem was the two-minute high, which film director Pasul Shrader described as “like falling down a dark elevator shaft.” The ascent was so fast and so intense that it made the descent that much more severe, and the desire to get high again that much more compulsive. This made freebasers frighteningly greedy— “like starving Dobermans waiting for red meat,” as writer Michael O’Donoghue characterized them.

The final problem was paying for the damn stuff. An ounce a day was common on a really bad jag, which would cost about $2,400. David Crosby’s habit eventually consumed a personal fortune of about seven million dollars.

“I sold that piano. I sold these guitars. I got them back, but there’s a story about them.”

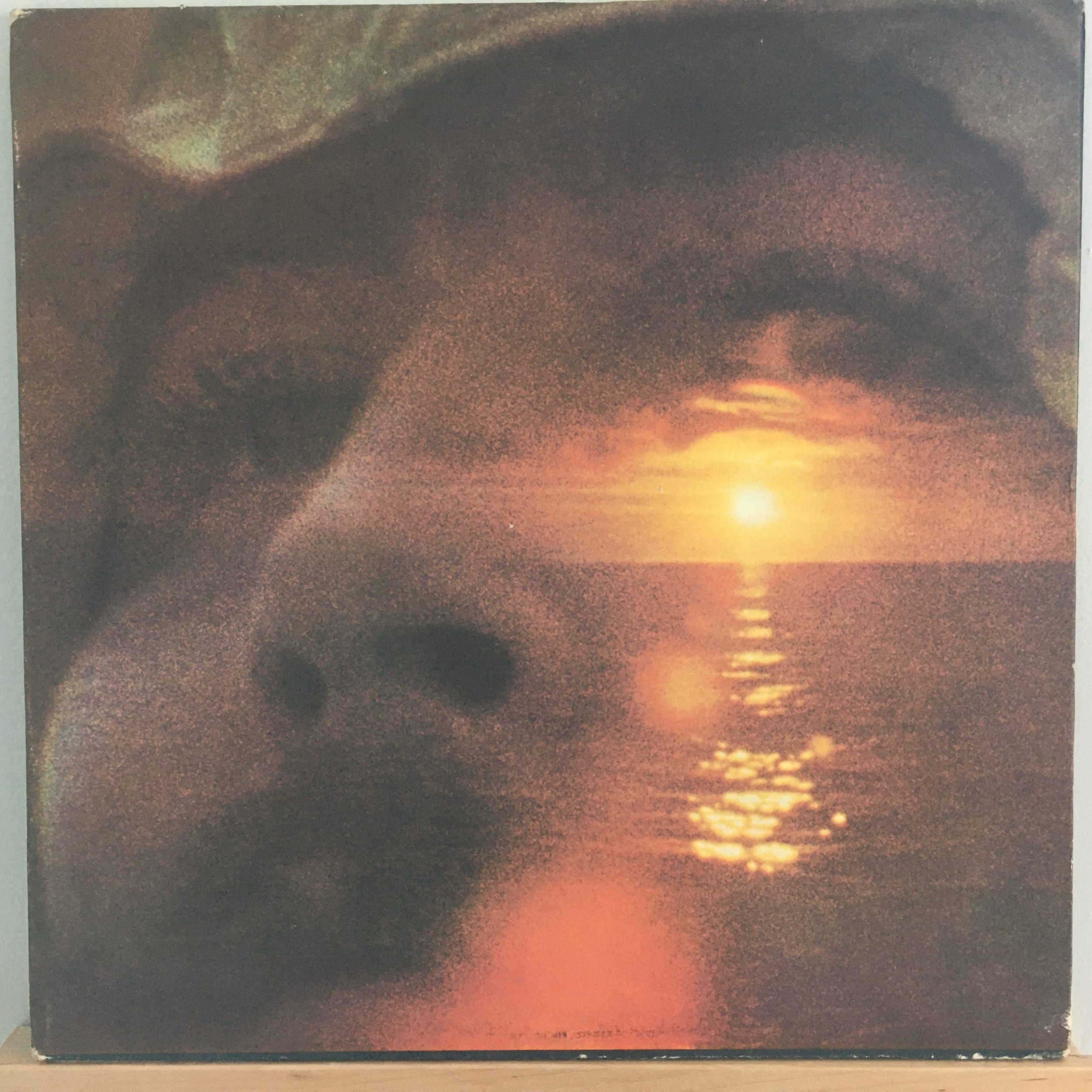

The guitar that Crosby was holding was a gorgeous vintage 12-string Martin conversion, purchased with the first money he ever earned as a performer, at clubs like Mother Blues. Crosby had played the guitar in the Byrds during those years when he was living in Laurel Canyon, cultivating the sybaritic lifestyle of his wildest fantasies—he was Lawrence of Laurel Canyon, as one of his friends called him—one of the princes of the new psychedelic spring. He later wrote such classics as “Long Time Gone,” “Guinevere,” and “Wooden Ships” for CS&N on that very guitar. At the nadir of his addiction, he took his guitars along to a hospital called Cold Forge in Altoona, PA.

“It was one of the places I tried to get straight, and when eight-thousand forty-nine minutes later I tried to get up and split—and believe me I counted every one of them! —there was a guy there who befriended me and my wife and said, ‘Don’t worry, I’ll send you your stuff,’ and went right out and sold my guitars. And that guitar, it was like losing your best friend. I tried everything; the guy was gone, the guitars were gone, the trail was cold.”

Over the next few years, Crosby served time in a Texas penitentiary and became one of the most public recovering drug addicts in America. Then he completed an autobiography—Long Time Gone, written with Cal Gottlieb—that will no doubt stand as one of the most authentic and powerful works ever published about the era of Sex, Drugs and Rock and Roll.

Throughout those years, much of what had been lost along the way was restored to him: career, self-esteem, friends. He purchased this home in Encino and fathered a boy named Django, but like a metaphor of his addiction, his guitar was lost—a continuing reminder that notwithstanding the wonders and gifts of a new clean and sober life, some things may never be recovered.

Once, outside a concert hall in Pennsylvania that he was playing with Graham Nash, his wife Jan saw a boy go by who she was certain was wearing a shirt of hers that had disappeared from the hospital along with the guitars. They brought the boy backstage, and it turned out he was engaged to a girl whose father had both guitars—an Armenian fellow who’d never taken them out of the cases the whole time he’d had therm. The promoters then called and tried to convince him to sell the guitars back to Crosby—everyone from the CS&N camp called and tried to convince him to sell back the guitars but the response was always then same: “Fuck you, I paid for them, I’m keeping them.” Then, with Crosby’s fiftieth birthday approaching, his wife decided to make one final attempt and asked Graham Nash, the diplomat of the group, to give it a shot. Nash came back downcast. “It’s hopeless, David. We will not get those guitars back.”

At the birthday party, where 200 of Crosby’s friends gathered to celebrate the miracle of his life, Glenn Close and Woody Harrelson approached him. “David,” Close said, “you know Woody plays guitar, and he would really love it if you would show him how to play one of your songs.”

Harrrelson then said, “Come on, man, I’ve got my guitar right over here.”

When Crosby opened the case, there was his darling Martin conversion.

“They set me up good! It was like my heart stopped when I saw it, and my eyers filled with tears.” He went silent for a moment. “You gotta be real bad to lose something like this…”

The costs of Crosby’s addiction were not over. Within two years, he would almost die of liver failure and struggle back yet again from the brink of death after a transplant. After that, he’d find the long-lost son he fathered out of wedlock back in the Sixties and form a band with him. And so it would go in his life: things lost, things regained with new meaning.

“I’ve had a lot of wonderful things happen to me in sobriety. Anybody who tells you that they got their life back isn’t lying.”

Cosby finger picked a few harmonic notes on the guitar--notes that flitted about the room and reverberated like beautiful sonic doves.

“That’s why they call it recovery.”